Steck Salathe: Understanding What it Means to be Between a Rock and a Hard Place

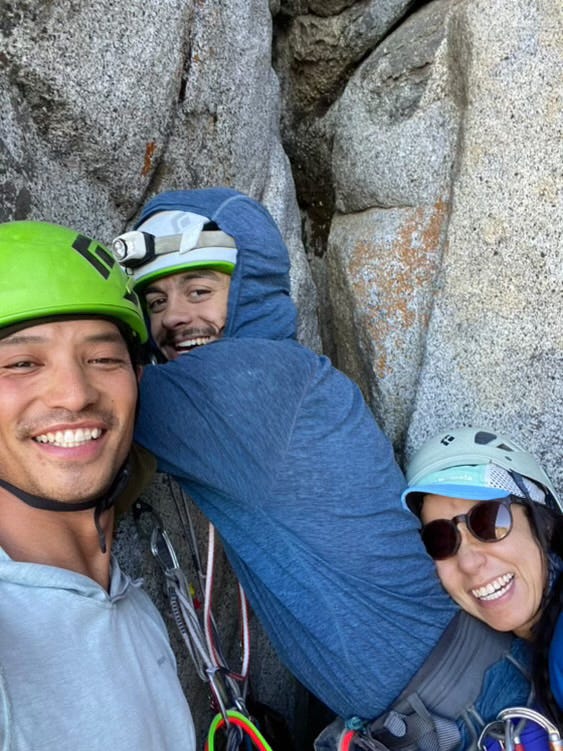

Hyped to welcome our newest contributor, Alonso Rodriguez, to The Drifter’s Journal! Alonso lives for the high places—walking lines stretched between cliffs, chasing big walls, and seeking out the kind of adventures that leave your hands sweating just hearing about them. He’s one of those rare souls who moves through the mountains with effortless flow, turning the impossible into just another day outside. We’re beyond stoked to have him on board, sharing a story from one of his climbing pursuits.

Give him a follow, and stay tuned—this one’s a good read.

Nearly 1000 feet above the valley floor, swallowed by the darkness of a vertical cave, it hits me—there’s no way out. I’ve made a terrible mistake. The kind you only get out of with a heroic helicopter rescue or a bodybag. We were lucky that YOSAR didn’t have to pull us out of that claustrophobia-inducing chimney or that we didn’t freeze to death on the summit. I vowed to be back there someday. Not soon, but someday.

How do we ever know we’re ready for our next challenge? Maybe that’s the point—we don’t. I’m not sure what exactly pulls me back to rock climbing as I’ve had my share of close calls. Moments in which death leans in and whispers, “Next time, you’re mine.” Even when I walk away unscathed, it lingers. In the dead of night, I jolt awake thinking about the runouts where a fall would’ve meant paralysis, a broken ankle would’ve required a helicopter rescue, or where hesitation in an unexpected storm could’ve meant a night spent unprotected in the wilderness. One moment, everything is perfect; the next, it can be a fight for survival. And yet, I keep coming back. I can’t explain it, but I also can’t picture my life without it.

Maybe that’s the whole point of an “adventure sport.” After all, if we knew what the outcome of every action was going to be, it just wouldn’t be an adventure anymore. This is my story of one of the scariest and coldest days of my climbing career to date.

It was a crisp August night in Yosemite Valley and our alarm clocks had just gone off at 2AM. We had slept only four hours or so and, for a split second, crawling back under the bushes that were our shelter to get another 15 minutes of sleep sounded really nice. Instead, we found ourselves packing up and driving to our trailhead.

None of us wanted to eat breakfast that early in the morning—Victor had a late dinner and Sarah simply wasn’t hungry—but we forced an oatmeal breakfast down so that we would have enough energy to complete the day. We were in for a long battle, that much was sure.

The Steck Salathe is what was on the menu that day. The route is known in Yosemite for many things. For starters it has a hard, dangerous approach where one slip can lead to your death before you even begin the real climbing. Once the real climbing begins, the route has 15 pitches, 12 of which are either offwidth or squeeze. Additionally, this route hosts the most famous vertical squeeze in America, known as the Narrows. Then, after all of that, remains a notoriously difficult descent—a steep gully with many rockfalls leading to a jungle that is confusing to navigate. To put this route in perspective, experienced climbers have lost their lives attempting this route—the approach took the life of a strong 5.12 climber, and free soloist Derek Hersey fell from the route itself in 1993, his lifeless body found at the base.

At the time we set out to attempt this route, we were all budding 5.10 Yosemite climbers, with only a few 5.10 leads under our belts. Our goal was ambitious, but nonetheless we were excited!

The approach fully lived up to the hype. We started up the trail after breakfast at roughly 3:30AM. By 4:45AM, we found ourselves on a sandy, slippery granite ramp that was only 4 feet wide and we were at a dead end. We were officially lost and had to backtrack down the sketchy ramp, where I envisioned my feet simply skating away from under me. Do you know that feeling when you stand near the edge of a cliff and you imagine yourself falling? Suddenly, you get some sort of head rush and the only way to calm your nerves is to step away from the edge and sit down. I felt that feeling tenfold while on this ramp, trying to down-climb and had no choice but to force away the anxiety and the intrusive thoughts of falling to my death. By the time we finally made it back to the base of the route at 5:30AM, I had just about exhausted all of the exposure that my brain could handle and we hadn’t even begun the real climbing yet… At this point, doubt had crept its way into my system. It was obvious that the rest of the team felt this way as well, but nobody voiced these concerns. In hindsight, this was likely a big mistake.

We regrouped and made a plan. Sarah would lead pitches 1-5 and get us past the “horrendous 5.9 squeeze chimney.” Victor would then take us past the technical crux of the route by leading us to the top of pitch 9. From there, I would lead us through the Narrows and up to the top of the formation.

Pitches 1-5 went well. Sarah led with confidence and we followed as fast as we could while climbing offwidths with heavy backpacks dangling from our belay loops. Victor began leading his block and after a few hours we realized that something wasn’t right. Victor is normally a very confident and strong climber, but this day he climbed with hesitation. It’s impossible to know exactly what’s going wrong when you’ve slept very little, haven’t drank much water, consumed very few calories, and are feeling all-around nervous, in general. Perhaps a mix of every one of these factors caught up to Victor because by the time we had reached the top of pitch 6, it was apparent that we were not going to make it to the summit before nightfall. We had gotten lost somewhere between pitches 5-6, which unfortunately wasted valuable time.

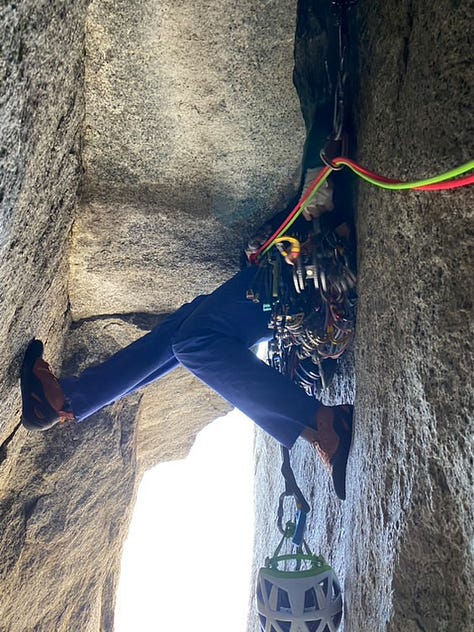

We were now standing on the formation known as the “Flying Buttress.” This buttress is accessed via its right side and then the climbable rock vanishes. In order to access more climbable rock, climbers must do a short rappel pitch off the left side of the buttress where more crack systems can be found. This is also the point of no return. After this point, bailing down becomes very difficult to do. We made our final mistake of the day here by deciding to continue moving up toward the summit of the buttress.

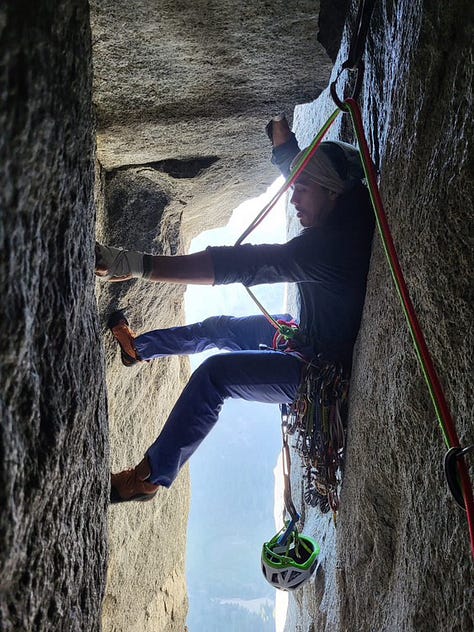

Victor led one more pitch and then decided he couldn’t handle the stress any further. He gave up his final two pitches and they were up for the taking. Sarah was also very tired by this point and had no interest in leading more pitches. It was up to me to lead us from pitch 8 all the way to the top of 15.

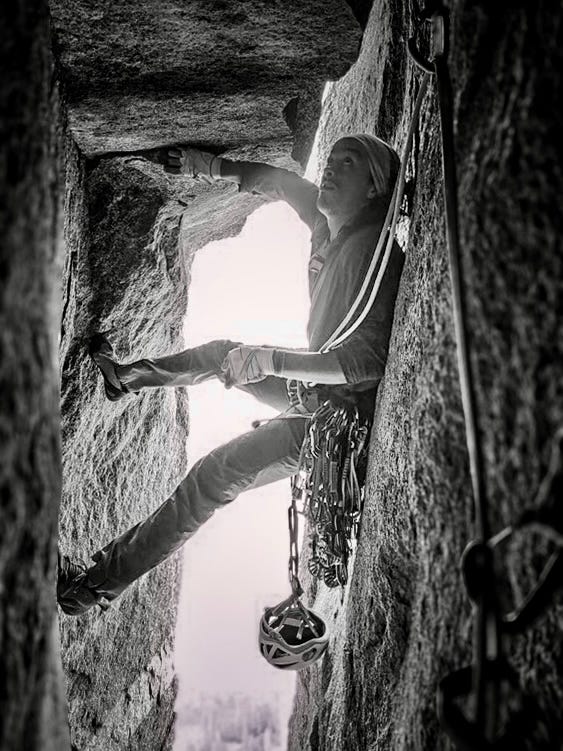

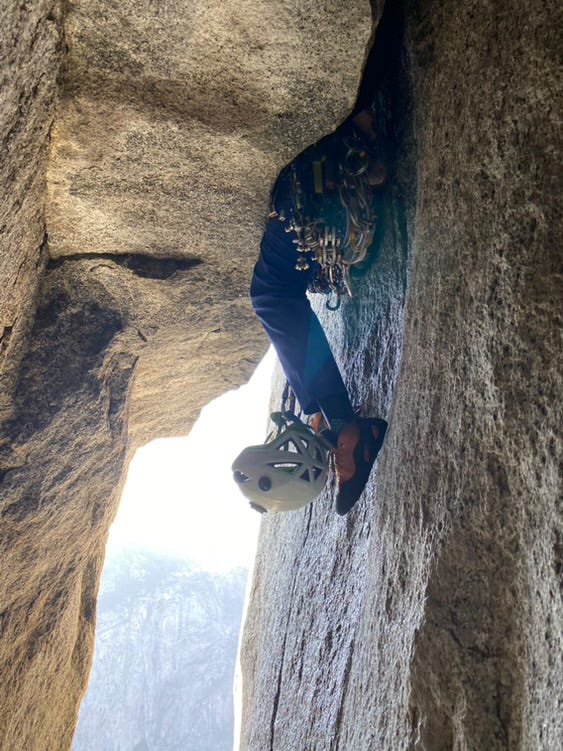

I led as fast as I could. I climbed boldly and confidently, moving quickly before my brain could feel the fear and placing gear only where necessary so as not to waste any precious minutes. My breaths quickly became short and shallow, my shirt drenched in sweat, and I had the biggest thirst on the entire mountain. To make matters worse, I was now standing at the base of the Narrows—a dark vertical chimney just wide enough to squeeze through, but tight enough to incite a panic attack. Imagine those videos where cavers have their cheeks pressed to the ground are trying to wiggle their way through… now take that cave and place it vertically near the top of a 1500-foot-tall formation. This is the Narrows.

The Narrows are so tight that you have to physically remove your helmet and dangle it below your waist on a long tether. A slot so tight that you have to turn your head sideways just to fit inside… I get claustrophobic to this day just thinking back on it. After a struggle with gravity, I wiggled my way in and thought Oh, this actually isn’t so bad. I’m having fun with how secure I feel right now. This lasted an entire 5 feet and then I noticed the constriction got tighter. I’m stuck. I’m stuck and I can’t move up or down, not even an inch. Panic began setting in. As far as climber physiques go, I’m a fairly large individual with a larger than average chest size. My background before climbing was bodybuilding and I was really regretting that life decision at this point. My panic became audible. At first, my climbing partners thought that I was joking. After a few seconds, they heard the fear in my voice and attempted to calm me by telling me to breathe and reset. So many things were running through my mind at this point. For one, it was getting dark and we didn’t have cell reception. My next thought was, Am I really going to spend the night stuck in this vertical cave?! After what seemed like an eternity, I managed to calm down. For a split second I even accepted my fate—I was comfortable at least and could wait for the search and rescue team to come get me. No, that’s stupid! I immediately corrected myself. I got myself into this and I should be able to get myself out. I wiggled around for a few more minutes and I used a distinct visual landmark on the wall in front of my face to tell me whether or not I was actually moving. I was not. I put out so much effort and I couldn’t squeeze my body in any single direction. It felt like the walls were closing in on me by the minute, and at one point, I convinced myself that they actually were and that the physics of the cold was making objects smaller and tighter as I had learned could happen from taking a physics class. I took a moment to relax—a deep breath in and then a deep exhale. Suddenly, at the end of my exhale, I moved. Not just an inch, but maybe two! Am I making this up in my head or did I really just move??? I figured it out! By exhaling all of the air out of my lungs, my chest became small enough to barely move up and down this death chamber. I reset and tried the maneuver again. To my surprise, and utter triumph, it worked! After repeating this many times, I found myself coming into the light at the end of the squeeze. I was free and thankful to God, in spite of not really being a religious person.

The Narrows took far too long. At this point, I had lost all hope that we’d make it to the summit before dark and was simply thankful that we had our headlamps. With barely any food and water left, we continued toward the summit and finally reached it at 11PM. We attempted to descend, but it was simply too dangerous of a gully to navigate in the dark. For safety, we decided that the summit was our home for the night. None of us expected the deep cold on an August night, but we were in for one of the worst and coldest nights of our lives. Cold sweaty clothes, no jackets, and only our flaked ropes to protect us from the freezing cold ground, we huddled together for warmth and it still wasn’t enough. We collectively shivered for 7 hours straight. At times, my body was so fatigued that I would fall asleep only to be woken up by my bones shivering against the cold, hard ground. We beat ourselves up pretty hard up there. Nobody likes to admit to failing to plan, but we did just that by not bringing any kind of emergency blanket or fire-making source. There was a literal endless amount of dry wood on that summit and I would’ve given my life savings just to have had a lighter and a few pieces of paper to start a fire with. At first light, I shed a tear of joy knowing that the warmth was nearer and the cold darkness was over.

The descent that next morning was surprisingly smooth and soon we were back at our car, stuffing our faces, too full to even speak to each other. A tourist stopped by and asked what we had just accomplished and we wordlessly pointed up toward the vertical chimney that nearly forced us to require rescue services. I will never forget the details of this climb. One day I hope to have the courage to go back and try this route again, but until then, I’ll find the right amount of adventure in the climbs within my comfort zone.